A Shot to the Heart, Part 3

The next day about six pm, Brian showed up at camp with his 10- and 12-year-old sons to take Lynn and Tracy up the Swift River to hunt moose. He was sure they were going to find one.

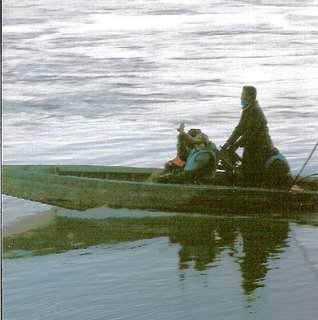

Watching them pile into Brian’s boat, I had some trepidation; it didn’t look seaworthy enough to get them across the river, much less up the Swift and back with a moose packed in as well.

Brian’s boat is a wonder to behold. It is an old hand-made wooden boat about 16 feet long and four feet wide, built of cedar planks and 2 x 4s. The bottom is plywood. There is no toprail for the gunnels, just a 1 x 3 grab rail level with the boat’s sides. Brian danced nimbly about the boat on these edges, hardly even making it rock. The two bench seats fore and aft of the stand-up driving station are removable 2 x 6” planks. The driving station is an open framework of 2 x 2s with a plywood front, which serves as a backrest for the front seat. The wood is old and leaky and the boat requires constant bailing. It is powered by a 40 HP Johnson 2-stroke with a jet foot; it only draws a few inches of water. It also has no reverse.

One of the boys pushed them back into the Kuskokwim and off they went. They cruised into the Swift River and made their way past bend after bend in the river with Brian sweeping confidently around each turn. Suddenly he pulled the boat to the bank and cut the motor.

“There it is—moose! Right there! Can you shoot it from here?” he whispered tersely.

Lynn was up in a blink, rifle to her shoulder sighting through the scope. About 85 yards away, a magnificent bull moose stood at the edge of a dry wash, munching on willows. He was turned directly towards them, displaying a full frontal view of his eight-tined rack, his head and his chest. As she sighted in on him, he stood, immobile, offering.

“Thank you” she whispered as she squeezed off a first shot and then a second.

From that distance she couldn’t tell where she had hit him, but in a moment she would know; the first shot had done it—a shot to the heart.

He turned and took a few slow steps. Brian moved the boat around a point and he and Lynn were out and racing through the trees toward the moose in a flash. They watched as the huge animal dropped, all movement stilled. The two hunters stood over the moose in silence, offering thanks.

Lynn had some time alone with him afterward as Brian went back to move the boat up, get the knives, and bring Tracy and the boys to help. Now the work would begin.

After three long hours of hard labor, the moose was butchered using only two Bowie knives and a Leatherman, and the meat was packed in the boat with the head riding on top. Daylight had disappeared completely. Now all they had to do was take a very heavily laden leaky old boat down the Swift River in the dark and get it back to camp to unload 600 pounds of moose meat. Hey, no problem. After a few ballast changes to achieve optimum balance they were off down the Swift, with Brian skillfully plowing through the curves and barely shipping any water.

As light disappears from the land at the end of the day, the river draws light from the sky into itself until the water seems to glow in the dark as if it lit from the earth’s inner fires; Brian used that light to read the river as easily as a well-known poem.

They pulled up at our camp about 10:30 p.m. and quickly unloaded the moose onto a tarp on the beach and covered him. The boys bailed for a minute or two while Brian gulped some warm coffee and then they were off into the darkness, bound for Stony River. The boys had school the next day.

We retired to the fireside for warm drinks and rest and silence after they left. Lynn was so tired she could barely stand up, but was still so wired from the experience that she could hardly sit still. She paced for a bit and then came to sit beside the fire with me.

“It was so incredible,” she said several times. “So absolutely incredible.”

Tracy was very quiet. She simply nodded at this. Taking the animal’s offering had been a profound experience for both of them.

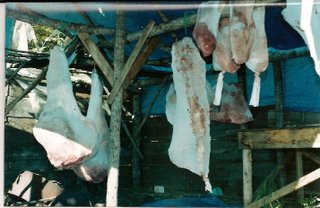

The next day was the Ides of September, the 15th of the month. It could have been 20 degrees and snowing or 35 degrees and raining; instead it was 50 degrees and sunny, with a fresh breeze, and we counted our blessings one more time. Brian said that moose hunting season around here is generally one long month of endless cold rain, no fun to be out camping and tromping through the woods in. But we had not only a full moon to camp under, we also had the most perfect Indian Summer weather imaginable. Nearly cloudless blue skies and bright sun for 12 to 14 hours each day, warm air cooled by a light steady breeze; dreams of camping don’t get any better than that. It was perfect weather for hanging the moose to dry for a few days; he would be significantly lighter by the time we packed him in the boat to go home.

After a big breakfast of pancakes, bacon and eggs, we started the next stage of moose preservation. It took the whole afternoon to transport the pieces off the beach and up to the drying shed, hang them, wash them with river water and then spray them with a citric acid solution, and finally wrap them in game bags. Lynn’s dog Jack did his part in harness, helping pull the meat-loaded sled from beach to drying rack, about 50 yards. Not a great distance, but 600 pounds is a lot of moose. The Little Dog, Pepper, ran back and forth between beach and shed, offering encouraging barks, very excited by the sight and smell of so much meat. We all three worked hard that afternoon, getting the mountain of moose meat hung, washed and wrapped. I kept the fire going all day so there was hot water for washing and fresh coffee always ready.

Our food supplies included fresh potatoes, carrots, and onions; so with chunks of fresh moose meat and a gallon of filtered water from the rain barrel, I cooked us up a great stew for dinner. By 8:30 we were all three tired to the bone and headed straight for bed. We did get short and much-needed showers first with heated river water funneled into the solar shower bags.

Our food supplies included fresh potatoes, carrots, and onions; so with chunks of fresh moose meat and a gallon of filtered water from the rain barrel, I cooked us up a great stew for dinner. By 8:30 we were all three tired to the bone and headed straight for bed. We did get short and much-needed showers first with heated river water funneled into the solar shower bags.Fresh meat needs to hang for several days, so we had some time for R&R before starting the long trip home. The hunting was done, the moose was hanging, it was two days until we left and we had the following day to pack. That left us one entire day for going fishing, taking walks, picking berries, reading, sleeping, whatever we wanted. It had been very windy for several days, probably portending a big change in weather, but so far the sky remained blue and the sun bright. We were hoping like mad for just a few more days before it crashed. In his thirty years of moose hunting on the Kuskokwim River, our friend Henry has many stories of straggling home through rain, snow, sleet and hail. Eventually, we probably would have similar stories, but this first time on our own, it would be nice for this trip not to be one of them.

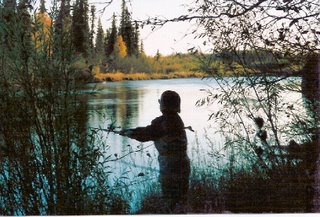

In the afternoon, Lynn and Tracy took the Zodiac across the river for some rod-and-reel fishing while I stayed in camp to read and do some writing. They had been gone about two hours when I heard the buzz of a small boat coming up the river. It was Brian, and the Zodiac pulled in right behind him. He wanted to go back up the Swift and look for another moose, this time for himself. He easily admitted that he is not a very good shot and hoped Lynn would be his shooter. Alaska game statutes allow for a proxy shooter, so she would not be in violation of any game laws if she shot a second moose as long as it went to someone else. If we got one, he said, we would simply gut it and leave it there; he would come back the next morning with a couple of his friends to butcher and pack it out. The meat would be more tender and succulent for being allowed to age without the trauma of movement for 12 hours or so. And the wolves were pretty far back this year, so he was not worried about predation overnight.

This was my first experience with Brian’s boat, and on close inspection one must seriously question whether it was safe to get into. With its low sides and constantly seeping water, it looked like it could swamp awfully easily. The wooden planks were worn and I couldn’t help thinking “my God, if we hit a rock we’re going to go to pieces!”

Oh well. We all hopped in, of course, and were away like a shot. Brian drove his boat like the sports car it was, a craft perfectly adapted to the job it must perform. We were into the mouth of the Swift in no time, skirting obstacles easily, flying around curves on the shallow inside corner, shooting over rapids that seemed impossible. He knows the river like the shape of his own hands, and negotiated the narrow channel with skill and style and complete ease, and did it wearing a boyish grin most of the time because he was really having fun.

We stopped at the spot where our moose died and took some pictures. Brian found Tracy’s camera on the ground under some leaves where it had been left behind in the gathering darkness when they butchered the moose. Two days in the elements didn’t seem to have damaged it.

A little further up the Swift, Brian pulled in at his dad’s second camp, a simple cabin and a steam bath made of logs high up on a knoll with a breathtaking view of the Swift and Sunitna Rivers, and the Alaska Range in the distance. The Swift has its origin in those mountains. It is such a gorgeous spot that I wanted to just stand and drink in this view for a long time. Blogger refuses to load this photo.

We were quickly off again upriver. The water was so clear you could see rocks and sticks three feet down. It was bracingly cold.

We turned into the Sunitna and the current slackened perceptibly. It is pure, clear, cold water also, narrower than the Swift, with more trees right at the bank. There is a house-sized boulder on the left side with a lovely camping spot beside it. This is where Goosma figured we would pitch the wall tent if we made it this far up in my boat. We jumped out for a little rod-and-reel fishing, but nothing was biting, so we were off again.

Quite a bit further up, Brian showed us Goosma’s land. After what we traveled through to get here, we were amazed that Goosma thought we could get my big boat and motor up here.

“He sure has a lot of confidence in us,” Lynn commented.

A little further up, Brian told us, is a great fishing hole; so of course we had to try it. Cruising on step, he turned into a tiny slough without even slowing down. We rounded a curve and two trumpeter swans rose from the water and slowly flew off. They were huge and beautiful. I couldn’t get my camera out quickly enough to capture them.

The pool they had been swimming in was quiet and deep. Clearly visible at three to four feet deep we could see a dozen ruby-red salmon swimming in circles. They were silvers (coho) who had finally reached their spawning stream. Salmon live most of their lives in the ocean and return to the fresh water streams of their birth to spawn and die. It is a biological imperative to which they give maximum effort. As soon as they enter fresh water they begin a slow and inexorable process of deterioration which begins with color change. They come from the ocean completely silver and begin to turn rosy pink and then more and more red. Their bodies start softening; eventually they can rot while they are still alive.

We cast lines for about 15 minutes and Tracy landed one. The color was incredible. But even more incredible was his nose. It was grotesque. It was a malformed, upward sweeping snout, some two inches long. It looked bizarre; his softening process was moderately advanced, but he was still firm. Brian said they still taste great at this point in their life cycle and took this one home for dinner, since we did not need the food.

Light was fading fast when we turned downriver to head home. By the time we were halfway down the Swift, there was very little light at all, and it was really chilly. Brian drove full speed ahead, skipping expertly around snags and boulders, following the current with the unerring sense of long experience. We pulled into our camp nearly frozen as total darkness engulfed us and the waning moon rose. Brian pressed on for Stony River without even waiting for hot coffee.

...to be continued...

Labels: Tundra Life

3 Comments:

Hi, Great writing, I love the story and can "feel" your experiences.

In New Zealand there are no moose but we have an introduced Wapiti which is a smaller version. Much less severe environment here but I can relate to your river travels..

The reason for my comment.. What is the function of the citric acid wash of the moose meat.??

Do you wrap the meat in plastic bags?? (= polyethylene).

I'm sure you have a long list of "entranced" readers.

David--so glad you are enjoying the story! The reason for the citric acid wash is two-fold: it slows bacterial growth that causes meat to spoil, and it forms a hard "crust" on the surface of the meat that makes it resistant to flies laying eggs. The older method of meat preservation was to coat the surface of the meat with ground pepper, which also works. The meat is stored in cotton bags for hanging to dry and transport home; this allows air to circulate, which helps to keep the meat cool and dry, which is essential.

Wow.. i learn so much from reading your blog.. thank you for the great story!!!

Post a Comment

<< Home