Note: If you read this post before Monday, Oct. 23rd, photos were added after I received permission from the family and Father Gregory.

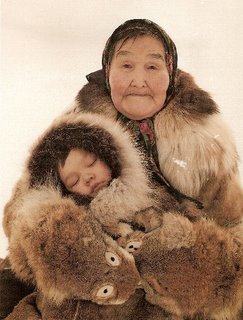

One of my patients died last week, in the small Yupik Eskimo village on the Yukon River where he had lived his entire life. Sergai was a relatively young man, in his fifties, who had intermittently been quite ill over the last two years. Recently, though, he had been doing well. His death came as a surprise and a shock to all of us.

Every death in a small village is deeply felt by all. The great majority of people in a village have lived there for their entire lives, and everyone not only knows everyone, but is also somehow generally related to everyone. When someone dies, the life of the village comes nearly to a halt until that person is buried. It is as if the village holds its collective breath for three days.

There is no “funeral industry” in any village, or in Bethel. No funeral homes, no undertakers, no hearses, no grave-digging services, no florists. If there is no suspicion of foul play, then no autopsy will be done, and the body of the deceased will remain at home. Family members will wash and dress the body (gender specific; men will wash the men who die, women will wash the women). Some of the men in the village will build a box to be the coffin, and the women will line it with the nicest fabric they have. Several men with shovels and pick axes will dig the grave; in the winter it may take two to three days to dig a hole deep enough.

The coffin with its occupant will lie in state in his or her home for two days. Candles will burn constantly and the family will keep a vigil the entire time. Villagers will come and go, bringing food, offering comfort, praying, frequently kissing the deceased. Tears and whispers prevail.

On the day before the funeral, the coffin is moved to the church and placed in the center of the sanctuary. The vigil is maintained by extended family and friends, and the deceased is never left alone.

The funeral is held on the third day after death, and most of the village attends, regardless of faith; half the village is Catholic and half is Russian Orthodox. Sergai and his wife Beatrice are Orthodox. The family requested that I attend the funeral; I was honored to do so, and very pleased that Dutch was able to attend with me. It meant a lot to the village that we came.

This was my first experience of an Orthodox funeral. Dutch and I flew to the village on Wednesday morning, carrying boxes of food as gifts for the family. We arrived just before noon, and by the time we were dropped off at the clinic, word had already spread that we had come. Several people called immediately to see if they could make an appointment with me. The health aides said no, I wasn’t there to see patients, only to attend the funeral; but in the two hours before it started, one patient did come in to have me inject her bad arthritic knee.

I had asked one of the health aides what to wear for the service, and she simply said “Kuspuk!”

Duh. Of course. So I wore my favorite one, a blueberry-print fabric that my mother made for me. And jeans and mud boots. “Dressed up” has a whole different context here, and elegant footwear is senseless. Dutch and I caught a ride from the clinic to the church on the back of a four-wheeler, and arrived with mud spatters to our knees.

The big, deep-throated bell next to the church was tolling loudly as we entered. The church was about half full. There are no pews or chairs in the Orthodox church; the congregation stands for the entire service. And the Orthodox are known for looooong services. There are two tiny benches along the back wall for elders who are unable to stand. The congregation is gender segregated; men stand on the right and women stand on the left.

The altar at the front of the sanctuary is behind a wall, and only the priests and altarboys may go through the door. The door remains closed except during the actual service; the congregation can only see the altar when it is open.

Almost the entire service consisted of prayers chanted/sung by Father Gregory, the village priest, two assistant priests, and the lay reader, Father Gregory's wife Janet. And though the prayers were in English, I could not understand most of the words. Several phrases repeated often, and those I could understand. Many times Sergai was referred to as being asleep. The opening prayers lasted for about an hour and a half. The congregation occasionally sang a response and frequently made the sign of the cross upon themselves, but there was no kneeling. And no sitting.

When prayers were done, the entire congregation was led by the priests and then the widow and then the immediate family to file past the coffin one by one and kiss the deceased’s forehead, his lips, and the icon image propped on his chest. Small children were lifted up by their parents to kiss the dead man.

This part took a while, as the church was quite full. Dutch and I stood quietly watching, and I was very aware that we were the only non-villagers (i.e., Caucasians) in attendance. He looked down at me with eyebrows raised and whispered “I don’t think I need to do this part.” I listened to the coughs and sniffles all around me and wondered whether I could. In the end I went up as the last person in line. I leaned close to his face and whispered goodbye to him, but I couldn’t kiss him. It was enough, and it mattered to the family that I participated. His niece later showed me the photo that she took of me bending over the coffin.

This part took a while, as the church was quite full. Dutch and I stood quietly watching, and I was very aware that we were the only non-villagers (i.e., Caucasians) in attendance. He looked down at me with eyebrows raised and whispered “I don’t think I need to do this part.” I listened to the coughs and sniffles all around me and wondered whether I could. In the end I went up as the last person in line. I leaned close to his face and whispered goodbye to him, but I couldn’t kiss him. It was enough, and it mattered to the family that I participated. His niece later showed me the photo that she took of me bending over the coffin.

After the kissing was done, the main priest gave a short homily about the impermanence of life and the importance of living each day so that you could be proud if it were your last. Another prayer ended the service, and eight strong men came forward to carry the coffin out to the graveyard behind the church. Beatrice walked behind them with her hand on the coffin. Because Sergai had been a veteran of military service, his coffin was draped in an American flag.

At the graveside more prayers were said. Seven men from the village (who I think were all veterans, but they were not in uniform) fired a 21-gun rifle volley over the river. The flag was folded military style and presented to Beatrice. The eight strong men used ropes to lower the coffin into the grave.

.

A plywood box covered in plastic sheeting had been constructed to fit over the coffin, and this was lowered on top of it. When I asked someone about this later, I was told it was to “protect” the coffin. I wondered…why?

.

.

Then the eight men picked up their shovels with a load of dirt and walked around the grave offering anyone who wanted to take a handful of dirt and throw it into the grave. The congregation and the priests remained at the graveside until the shoveling was done and the grave was filled. Only then was the funeral concluded.

.

.

A feast was held at Sergai’s house afterward, and Dutch and I were invited to come. It was not your average potluck; ritual was involved here too. A table was placed in the center of the main room where his coffin had been before it went to the church. The table had eight chairs around it. The room was packed with people, but no one sat at the table. Father Gregory led a lengthy blessing, then the three priests seated themselves at the table with the oldest men present. The women of the family served them food. No one spoke; the room full of people was completely quiet. After they had eaten, all eight men stood up as one and left the table. The younger men came forward and sat down. As honored guests, Dutch and I were invited to join this seating, along with the oldest woman present, Beatrice’s mother.

The food was delicious. There was a thick whitefish chowder, moose soup in a clear broth with noodles and vegetables, cole slaw, potato salad, macaroni salad, several kinds of bread, sliced ham, and lots of desserts, including homemade tundra blueberry pie.

The cultural expectation at a feast is to come in, eat and leave. Houses are small, and once you have eaten you need to clear out and make room for the next person. So when we finished eating Dutch and I left; it was about 7 pm, and just getting dark. The feast went on for several hours, until everyone who wanted to eat had been fed. The family will feed the village twice more in the upcoming weeks, at a 20-Day feast and a 40-Day feast. And forever after, they will hold an annual feast on the anniversary of Sergai’s death.

After the feast, Dutch and I returned to the clinic where we would stay overnight. Scheduled plane service to the village is limited to twice a day and the last plane leaves about 4:30pm. We could have chartered a later flight, but that would have cost over $600 one way. The clinic has an itinerant sleeping room with two bunk beds in it, so we brought sleeping bags and were glad for a slow internet connection and flush toilets.

Around 9 pm, Father Gregory's wife Janet called over to see if I would like to come and “mukiaq” (take a steambath) with her and some other women. I’ll almost never say no to a steambath, so I was delighted. I grabbed my towels and steam hat and left Dutch happily surfing his blogs. It was midnight when I returned, with skin glowing red from the heat and the quiet satisfaction of enjoyable time spent with people I have come to care about.

Our plane back to Bethel was slightly delayed by fog the next morning, but we were home before noon without any problem. As soon as we left, I missed the village. I love the closeness and supportiveness of the people there for each other. There is a tremendous bond among people from the same village, and it provides an incredible level of emotional support to each individual villager. Surrounding and suffusing that bond is the very strong sense of tribal identity that Yupiks feel because they are Yupik. In a melting pot world, they have a relatively intact culture that is thousands of years old. I can never truly be a part of their culture because I was not born into it; but I am incredibly grateful for what they so warmly share with me.

Note: I spoke with Beatrice and with Father Gregory on Monday morning, and both gave permission for me to post these photos. I thank them for allowing me to share this deeply personal experience with you.

Labels: Tundra Life

A fiendishly clever and totally delightful edition of Grand Rounds is up at the aesthetically tasteful blog of Dr. Michael Hebert, Dr. Hebert's Medical Gumbo. Dr. Hebert is a Cajun physician, formerly a resident of New Orleans, displaced since Hurricane Katrina to a community in Mississippi. He is an excellent writer and crafts his posts elegantly; I encourage TMD readers to spend some time browsing through his archives. You won't be disappointed.

A fiendishly clever and totally delightful edition of Grand Rounds is up at the aesthetically tasteful blog of Dr. Michael Hebert, Dr. Hebert's Medical Gumbo. Dr. Hebert is a Cajun physician, formerly a resident of New Orleans, displaced since Hurricane Katrina to a community in Mississippi. He is an excellent writer and crafts his posts elegantly; I encourage TMD readers to spend some time browsing through his archives. You won't be disappointed.