Alaska is America’s Last Frontier, and living here has all the flavor of frontier life that most people associate with movies about the Old West. Things are not as polished and genteel here as in most places in the Lower 48, especially for those who live “in the bush.”

Alaska is America’s Last Frontier, and living here has all the flavor of frontier life that most people associate with movies about the Old West. Things are not as polished and genteel here as in most places in the Lower 48, especially for those who live “in the bush.”

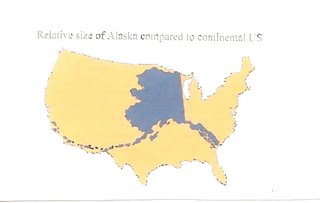

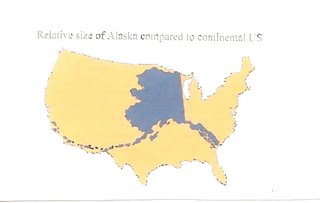

The state of Alaska is huge on a scale that is difficult to comprehend. I particularly like this graphic, as it puts size somewhat into perspective. Alaskans like to say that if you cut Alaska in half, Texas would still be the third largest state. Alaska has 600,000 square miles and 600,000 population, which works out to one person per square mile. But considering that over half the population lives in the three urban centers of Anchorage, Fairbanks, and Juneau—less than 10% of the land—once you leave those centers the population density is more like one person per five square miles. Or something like that, math was never my strong suit. Big, open, and empty of people at any rate.

In all this land there is only a very limited road system, mostly in the central portion of the state connecting Anchorage and Fairbanks (600 miles apart) and the Kenai Peninsula. This little road tangle sprouts off the end of the Alaska Highway, which meanders a few thousand miles down through Canada and connects up with the US highway system along the northern border of the Lower 48. That is a beautiful drive, if you’re interested, but don’t go unprepared. Anyone considering it should buy The Milepost, a guide to driving the Alaska Highway, available from Amazon.com and many bookstores.

Once you get off the limited road system in Alaska, you are considered to be “in the bush.” And now we’re talking truly rural, and very frontier. Goods and services are far more limited, and more expensive. The focus of life is much closer to survival and much farther from elegance. Climate plays some role in that, but distance and geography are huge factors also. Bush Alaska is the edge of the planet in many ways.

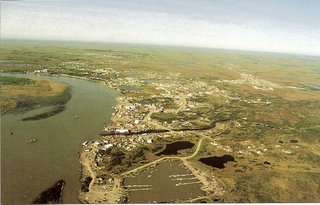

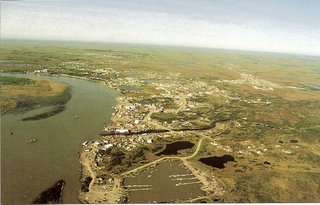

Out here on the edge is the town of Bethel. With a population of about 6,000, Bethel is one of the larger towns in the bush, along with Dillingham, Nome, Kotzebue, and Barrow. Bethel is the hub of southwest Alaska, a somewhat grubby little town (I say that with the greatest affection) perched at the edge of a huge, untamed (unbridged, undammed) river, surrounded by a gazillion miles of open tundra. Truly “out there” in every possible way.

The only way to get here from the Outside World is to fly in, from Anywhere to Anchorage, and from Anchorage to Bethel. Anchorage is very much like any other small Big City in the US (pop. 250,000), only with more gorgeous scenery. Prices are a bit higher, but availability of goods and services and the general feel of life are about the same as in any urban area of the Lower 48. Those who don’t live in Anchorage consider it a suburb of Seattle, and not “living in Alaska” at all. When Bethel folks want to really shop, or see a recently released movie, or eat in a nice restaurant, they “go to town,” which means they go to Anchorage.

Going to town is not cheap. The one-hour flight (400 miles) on Alaska Airlines costs around $500 for a round trip ticket. Occasional specials may drop the price to $300 or so, but those are not frequent. Traveling on to the Lower 48 is also not cheap; round trip Bethel to Seattle is $900 and takes eight hours each way; Bethel to Orlando is $1400 and takes 18 hours. Trips are carefully planned, and most people here don’t travel all that much. We don’t just pop over to Anchorage for the weekend on a whim.

Some people say that there is a time warp between Anchorage and Bethel, and once you land here, you’ve gone back about thirty years (or fifty). The pace of life is slower. Attitudes are different. The flavor of Yupik Eskimo culture informs everything about life here.

There are four Alaska Airlines jets from and to Anchorage on most days, weather permitting. The airport has two runways. The Alaska terminal has one big room where you check in and wait for your plane; security screening happens just before you walk through the door outside onto the tarmac to board. When you fly in, baggage claim is in the same room, so while you wait for your luggage,

you can chat with people who are flying out. Turn-around time from touch down to lift off is only about 40 minutes, so it happens pretty quickly. Opportunities to come or go occur at 8 am, noon, 4 pm, and 8 pm. You can see the jet land and take off from anywhere in town, and even though you may not want to leave, there is a sense of reassurance in that visible confirmation that the lifeline is intact. A few days without a jet and the grocery store shelves are pretty bare; we are very dependent on the connection.

you can chat with people who are flying out. Turn-around time from touch down to lift off is only about 40 minutes, so it happens pretty quickly. Opportunities to come or go occur at 8 am, noon, 4 pm, and 8 pm. You can see the jet land and take off from anywhere in town, and even though you may not want to leave, there is a sense of reassurance in that visible confirmation that the lifeline is intact. A few days without a jet and the grocery store shelves are pretty bare; we are very dependent on the connection.

The airport is about three miles from the center of town, and the ride in is bumpy one. Much of the road is paved, but laying pavement on tundra is not like paving hard ground; tundra shifts, heaves, and moves with temperature variations. We are living on a permanent ice cube covered with a mud layer and topped with a thick carpet of shallow-rooted plant growth. Roads buck and pitch and don’t stay where you put them.

Houses do the same thing, and one of the odder aspects of living here is that you have to have your house leveled every year or so. Frost heaves cause the foundation to shift, and suddenly your doors and windows don’t close anymore. Houses here are all built up on pilings (no such thing as a basement in Bethel) similar to beach houses in the Lower 48. When the door won’t close right, or there is a new crack in the sheetrock, it’s time to call one of the house leveling companies. They will come over and jack your house up, stuff a few shims on the piling, and ease it back down. And charge you three to four hundred bucks, depending on how unlevel it is, how big it is, and how long it takes them.

The shifting ground is also the reason that Bethel does not have an underground water and sewer pipe system. Until about ten years ago, there was no piped water or sewer at all. In the mid 1990s, a huge construction project was begun to bring piped water and sewer to Bethel, and about a quarter of the town now has a piped system. The pipes cannot be buried, however. They are built on top of the ground, and are somewhat of an eyesore, but you sort of get used to them.

People without piped water are on the hauled water system. Each home has a large water tank, usually 500 to 1500 gallons. The town operates a fleet of trucks that deliver water to the homes  once or twice a week. (I took this photo of a water truck getting filled at the pump house last December; the driver is holding "Flat Stanley" for a project that I was helping with.) A thousand-gallon water tank is about 8 ft. long by 3 ft. wide by 7 ft. high, and most tanks are inside the home to prevent freezing. Water conservation is absolute; you do NOT want to run out of water. When you turn on a faucet, you hear the water pump start up, and you become very attuned on a subliminal level to that sound. If no one is taking a shower or doing laundry, the pump should not be running for more than a minute; if it does, start looking for the source of water loss. A leaky toilet will empty your water tank faster than you’d ever think possible. No letting the water run while you brush your teeth. No cavalier approach to doing dishes. No long, hot, 40-gallon showers. No flushing the toilet when all you did was pee.

once or twice a week. (I took this photo of a water truck getting filled at the pump house last December; the driver is holding "Flat Stanley" for a project that I was helping with.) A thousand-gallon water tank is about 8 ft. long by 3 ft. wide by 7 ft. high, and most tanks are inside the home to prevent freezing. Water conservation is absolute; you do NOT want to run out of water. When you turn on a faucet, you hear the water pump start up, and you become very attuned on a subliminal level to that sound. If no one is taking a shower or doing laundry, the pump should not be running for more than a minute; if it does, start looking for the source of water loss. A leaky toilet will empty your water tank faster than you’d ever think possible. No letting the water run while you brush your teeth. No cavalier approach to doing dishes. No long, hot, 40-gallon showers. No flushing the toilet when all you did was pee.

The other half of this system is hauled sewer. Each home has a sewer tank (outside), emptied weekly by the town’s fleet of sewer trucks. Each truck evacuates three or four sewer tanks and then drives out to the sewer lagoon for emptying. We have no sewer treatment facility; ours is said to be the second largest sewer lagoon in North America.

It is the homeowner’s responsibility to keep the access pipes for water and sewer unfrozen and easily accessible to the big trucks. The last thing you want is to come home from a day’s work to find you’ve been “green tagged” by the water or sewer truck driver. Then you have to get out the propane torch, melt the ice blockage, and call the Dept. of Public Works to schedule another delivery or evacuation.

Until very recently (like only a few years ago), many homes in Bethel did not have sewer tanks or toilets. They had honey buckets. Literally, a five-gallon plastic bucket with a removable toilet seat and lid. When the bucket got full, it was set in the home’s entryway and the sewer man came into the house and picked it up, dumped it into the truck, and set it back empty. If it froze, he left it there, and you had to warm it up enough to thaw before he’d take it. Large families might fill four or five buckets between visits from the sewer man. Bethel outlawed honey buckets about five years ago, but some renegade types still have them, and empty them in trash dumpsters around town (also illegal).

Garbage removal happens only at the level of the dumpsters; there is no home pick-up. Each home in Bethel pays $12 per month for the privilege of carrying its trash to the dumpsters of choice. There is one on nearly every corner, so it isn’t that hard. Bethel only has two garbage trucks, and they work six days a week keeping the dumpsters empty. Dumpsters are “adopted” by groups, or by the neighborhood they reside in, and are painted according to the whimsy of the adopters. That is a subject for a post all its own, as a new round of adoption is coming up this summer and the new paint jobs will make great photo subjects.

There are other “common conveniences” that Bethel does not have. No home delivery of mail; everyone has a post office box. No drive-up window at the bank; everyone has to go inside. No drug store; the only pharmacy in town is at the hospital, and all prescriptions are filled there. No alcohol of any kind sold in town; Bethel is “damp,” which means it is ok to have alcohol shipped in, but none is sold legally in town. There are bootleggers selling rotgut for exorbitant prices, but most people order deliveries out of Anchorage. It is a two-day process to drive your order out to the cargo handler at the airport and then return the next day to pick up the shipment. Most of the villages are completely dry, and no alcohol of any kind is allowed. Village safety officers are authorized to confiscate any alcohol brought to the village.

Shopping in Bethel is an experience in itself. There are two locally owned (not chain) grocery stores, and both carry a far more limited selection of fresh vegetables, meat, canned goods and other supplies than the average Safeway. At far higher costs. A gallon of milk is about $8. A nice New York strip steak goes for $10.79/pound. A box of cereal costs $7 or more. Bread is $4 per loaf. It is interesting to watch people go through the check out line. The customer’s level of astonishment at the amount due is inversely proportional to the amount of time s/he has been in Bethel. After a while you get used to the fact that the weekly grocery bill for two people will run about $300. It helps a lot when your freezer is full of moose, caribou, and salmon.

There are a dozen or so restaurants in town, and all are outstandingly mediocre. They all have roughly the same menu, with Chinese food, pizza and hamburgers figuring prominently. The only franchise restaurant we have is a Subway.

The pace of life is very relaxed. Nobody really dresses up for anything. The only suits and ties you’ll see are on lawyers in court. There is nowhere to go that requires “evening dress,” and somehow the overall impression of a gown is somewhat marred by wearing it with snow boots.

Entertainment is pretty much self-made. There is no movie theatre, no bowling alley, no video arcade, no shopping mall, no pool hall, no tavern, no skating rink. Visiting friends, having potlucks and barbeques, playing games and just spending time together is the primary entertainment.

The medical staff recruiters for the hospital have an info packet which they give to newcomers; it contains a sheet called Things To Do in Bethel. The list contains the following suggestions:

Ask KYUK about volunteering on the radio

Ask someone about the medicinal uses of plants

Check out videos from the library

Clean up around your dumpster

Go Fishing (Ice Jigging in Winter; Rod & reel in summer)

Go on a bird walk

Go out for lunch

Go to a sled dog race

Go to a dance (Fiddle Dance at the Armory or Sober Dance at the alcohol treatment center)

Go to a quilt guild meeting

Go to a softball game

Go to Hangar Lake and watch the floatplanes

Have a potluck

Help clean up a dog yard

Learn how to harness dogs

Learn some Yup’ik words

Learn the names of different tundra plants

Learn to cut, dry, and smoke fish

Learn to sew fur

Learn to use an ulu (Eskimo knife)

Learn which villages are where in the Delta

Look at the graves in the cemetery

Make a basket

Make a kuspuk

Pick berries

Pick up a bag of trash off the tundra

Plan a camping trip on the tundra

Play on the playground equipment at Pinky’s Park

Read an out of town newspaper at the library

Read the editorials in the Tundra Drums or the Delta Discovery, Bethel's weekly newspapers

Ride a snow machine on the bluffs

See how many different tundra flowers you can find

See what new books are at the library

Take a Yup’ik dance class

Take a walk on the frozen river

Try agutaq (Eskimo ice cream)

Visit the Bethel History Display at the Cultural Center

Visit the displays at Fish and Wildlife

Volunteer at Bethel Health Fair

Volunteer at Cama-i, the annual dance festival

Volunteer at K300 headquarters (the annual dog sled race)

Volunteer to read to children at the library during Children’s Reading Hour

Watch the barge unload

Watch the commercial fishing boats come in and unload huge totes of salmon

Exciting, no? Like I said, we’re on the edge of the planet here, and there is no place quite like it. I truly love it.

Labels: Life in Bethel