Last year about this time, I received an email from Uncle Bob asking me if I would be willing to help his best friend's grandson, Shawn, with a school project. The boy's second grade class was studying geography and social studies. The lesson plan was based on a popular children's book called Flat Stanley, in which a boy gets "flattened" by a bulletin board that falls on him, and his parents put him in an envelope and mail him to different places to have adventures. Uncle Bob asked if I would mail Shawn a post card from Alaska with a note on the back about his "flat" adventure here.I had never heard of Flat Stanley, but the idea fired my imagination so much that I wrote a whole children's story about Shawn's flat adventure in Alaska. I included photos of Flat Shawn doing the things described in the story, as well as postcards, a calendar of Alaskan wildlife, and a videotape of the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race. Shawn was delighted. His teacher may have been a little overwhelmed; I never heard anything back from her.Remembering what fun it was putting this project together, I decided to share it here on Tundra Medicine Dreams. I subsequently learned that the Flat Stanley project is a widely-used teaching tool in elementary education in the U.S. Any of you who may be involved with a Flat Stanley project are welcome to use Flat Shawn's Adventure (with appropriate attribution, please) as part of the project if you would like. As always on this blog, names have been changed.

Flat Shawn’s Alaskan Adventure

Flat Shawn’s Alaskan Adventure

My name is The Tundra PA, and I am a physician assistant who has lived in Alaska for almost ten years. Recently, I received a letter from my Uncle Bob, who lives waaaaaaay down south in Mobile, Alabama (where I used to live when I was in second grade). Uncle Bob told me about his young friend and next-door-neighbor, Shawn, who is in second grade. Shawn’s class is studying the regions of the United States by sending flat versions of themselves (based on the book Flat Stanley) to different places to visit.

“Would you invite Flat Shawn to Alaska to visit?” my uncle asked.

“You bet I would!” I told him. What a great idea Shawn’s teacher had to help the children learn about the different parts of our great country this way.“Hey, Shawn!” I said. “Fax your flat self on up here, buddy, and let’s have some fun, Alaska style!” And so he did.

Fun Facts About Alaska

The day that Flat Shawn jumped off my printer and ran to the living room window to look out, it was a really cold day. Like about twenty degrees below zero! Brrrrr! So we decided to stay inside where it is warm and toasty next to the wood stove and drink hot chocolate and learn some facts about Alaska for him to share with the class when he returns home.

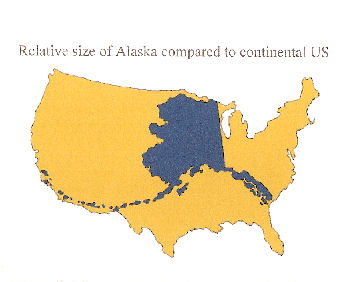

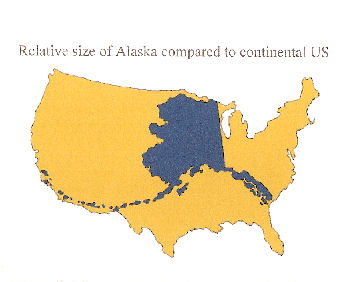

The first thing to know about Alaska is that it is big. Really, really BIG. If you could pick up Alaska like a piece of a puzzle, and lay it down on top of the “lower 48” (which is how we Alaskans refer to the continental U.S.), it would look like this:

“Wow!” said Flat Shawn. “It goes from sea to shining sea,” he said with a smile.

Alaska is the biggest state in the United States. It is over twice as big as Texas, the second largest state. North to south, Alaska is 1,400 miles long. East to west, it is 2,700 miles wide. It has almost 600,000 square miles and only 600,000 population. “That’s only one person for every square mile!” Flat Shawn said in amazement. “No wonder it looks so empty out there,” he said, gazing at the open tundra through the window.

“You’re right, Flat Shawn,” I told him. “In the lower 48 there are over 70 people per square mile.”

“How about the cities?” he asked.

“Well,” I told him, “Alaska has only three cities of any size. Anchorage is the largest, with 225,000 people (much smaller than Mobile!). Fairbanks is next, with 32,000 people; and the state capital, Juneau, is third with 30,000 people. Can you find those cities on our map of Alaska?” I asked him. And he did.

Alaska doesn’t have counties like other states do; it is just too big for that. The state is divided into regions like this:

The five regions are very different from each other. Southeast, South-Central, and Interior are full of huge mountains; 17 of the 20 tallest mountains in the U.S. are located there.  The tallest is Mt. McKinley, known simply as Denali by most Alaskans. At 20,320 feet, it is the highest point in North America.

The tallest is Mt. McKinley, known simply as Denali by most Alaskans. At 20,320 feet, it is the highest point in North America.

Southwest and Far North have only a few mountains that are much smaller than those in the Interior. These two regions have lots of flat, wide-open land called tundra, which is nearly treeless. I live in the small town of Bethel, in Southwest Alaska. The tundra here seems to go on forever, like being on a ship in the middle of the ocean. In fact, Bethel is kind of like an island, because you can’t drive here in a car. There are no roads that come here. You can only get to Bethel by plane or by boat (or by fax machine, if you are Flat). In Alaska, that is called “living in the bush”.

Alaska has two huge rivers and hundreds of smaller ones. The largest is the Yukon River; it is over 2,000 miles long. The second largest is the Kuskokwim (pronounced cuss’-ka-kwim), which is 800 miles long. Bethel is located on the Kuskokwim River, about 80 miles from the ocean. The river has all five species of salmon in the summer, and my friends and I love to go fishing for them. Fresh salmon is so yummy!

Alaska has two huge rivers and hundreds of smaller ones. The largest is the Yukon River; it is over 2,000 miles long. The second largest is the Kuskokwim (pronounced cuss’-ka-kwim), which is 800 miles long. Bethel is located on the Kuskokwim River, about 80 miles from the ocean. The river has all five species of salmon in the summer, and my friends and I love to go fishing for them. Fresh salmon is so yummy!

The Far North and much of the Interior are above the Arctic Circle. Flat Shawn quickly finds the Arctic Circle on the map. Those areas get very, very, very cold in the winter. Barrow is the most northern town in the U.S., at the very top of Alaska. In the winter it can get as cold as 70 degrees below zero! And when the wind blows, it feels even colder than that.

Besides being very cold, when it is winter in the Far North, it is dark all the time. Truly, it is nighttime 24 hours a day, seven days a week. The sun never rises at all, from mid November to mid January. It is very hard to know what time it is without looking at a clock. But the flip side of all that darkness is that in the summer, the sun never sets! It is bright daylight 24/7 from June to August. You can play softball or ride bicycles as easily at midnight as you can at noon—and people do!

“Wow,” said Flat Shawn, “you’d have to have really good clocks up there to know when to go to bed and get up. It’s hard to imagine.”

“You’re right,” I said. “Here in Bethel, we don’t have total darkness like they do in Barrow. For us, on the winter solstice (the shortest day and longest night of the year), the sun rises about 11:00 in the morning and sets about 3:30 in the afternoon. It stays low on the horizon and doesn’t get high overhead, but at least we get to see it. And in the summer, the sun rises about 4:30 in the morning and sets at 2:00 in the morning. We only have a few hours of semi-darkness each day during the summer. We play midnight softball too!”

“I want to come back in the summer and try that,” Flat Shawn said.

The other interesting thing that happens during the long winter nights is the Northern Lights. The scientific name for them is aurora borealis. They are usually green-blue in color, sometimes with pink, purple, or red mixed in. They wave and flicker in the night sky like a living curtain of color, blowing in a cosmic wind.

The other interesting thing that happens during the long winter nights is the Northern Lights. The scientific name for them is aurora borealis. They are usually green-blue in color, sometimes with pink, purple, or red mixed in. They wave and flicker in the night sky like a living curtain of color, blowing in a cosmic wind.

“I hope you get to see them while you’re here, Flat Shawn!” I told him. “We only have them occasionally, and you have to get up in the middle of the night to see them.”

“That’s ok with me,” Flat Shawn said. “I’ll wake up anytime to see that.”

“What about wild animals?” Flat Shawn asked. “Are there lions and tigers and bears around here?” He looked out the window with a worried frown.

I smiled and shook my head. “No lions or tigers. We do have bears, though. Mostly black bears around here, which are on the small side—for a bear, anyway. Alaska has lots of other bears, though. We are the only state in the U.S. that has polar bears.”

I smiled and shook my head. “No lions or tigers. We do have bears, though. Mostly black bears around here, which are on the small side—for a bear, anyway. Alaska has lots of other bears, though. We are the only state in the U.S. that has polar bears.”

Flat Shawn peered hard out the window, in case one was walking across the tundra toward the house.

“Don’t worry,” I assured him. “Polar bears aren’t here in Southwest Alaska; they are only in the Far North. Alaska also has grizzly bears and Kodiak bears, but not around here. And you wouldn’t see them now anyway, because it is winter, and they are hibernating.”

Flat Shawn breathed a sigh of relief. “That’s good,” he said. “I don’t think I want to see one close up.”

“We have other wild animals,” I told him. “We have moose, caribou, fox, wolves, wolverine, beaver and muskrat; and in the sea there are seals, walrus, and whale.” The Yupik Eskimo people who have lived in this region for thousands of years hunt these animals for meat and fur. The meat keeps them alive and the fur keeps them warm in one of the harshest climates on earth. When they hunt and fish, they are very careful to waste nothing, and to honor the spirit of the animal they hunt.

“Will I get to see a moose?” Flat Shawn asked.

“Maybe not moose, they are mostly way upriver from Bethel; but you might see caribou. There is a large caribou herd that lives fairly close. The herd numbers over 20,000 caribou, so it is not hard to find them. They wander around the tundra all winter, and sometimes come within 20 miles of Bethel, so maybe we’ll see them while we are out adventuring,” I said.

Flat Shawn turned away from the sunset filling the west-facing window and sniffed appreciatively. “Something sure smells good, and it’s making me hungry. Is it time for dinner?” he asked.

“Indeed it is,” I said with a smile. “I hope you like moose stew and cornbread.” After finishing seconds of each, it was clear that he did.

“Did you hunt that moose?” he asked after dinner.

“No,” I said. “I’ve never killed an animal, myself. That moose meat was a gift from a Yupik Eskimo friend who lives way upriver from here, in a tiny village. Only about 50 people live in that village, and they are all Eskimo. My friend’s name is Golga, and he is a very good hunter. He frequently comes down to Bethel and brings moose or caribou meat with him.”

“Will I meet any Eskimos while I’m here?” he wanted to know.

“Yes, you will. About half the people in Bethel are Yupik or Cupik Eskimo. I will introduce you to some of them,” I said. Flat Shawn’s eyes sparkled as he thought about all the new adventures he was going to have.

The next morning Flat Shawn was up early and ready to get started. “But it is still dark out!” he said disappointedly. “And it is after nine o’clock! When will it get daylight?”

“Oh, about 10:30 or 11:00,” I answered. “Plenty of time for you to have a nice hot breakfast and think about how to dress to stay warm.” It warmed up a little from yesterday; today it is only ten below zero. And tomorrow should be right around zero, which feels really warm after twenty below. The coldest I have ever seen the thermometer go to was forty below. That is too cold to even go outside. Cars don’t run well, and everybody just stays home to keep warm.

The key to staying warm when it is cold out is to dress in layers. And the best outer layer is fur. It has kept the Eskimos warm for thousands of years without any fancy high-tech gear. I find Flat Shawn a beaver hat, beaver mittens, and knee-high boots of wolf and caribou fur called mukluks. They were all made for me by an Eskimo woman who lives here in Bethel.

“Goodness, Flat Shawn, if these are going to fit you, we need to make a full-boy-sized version of you,” I said. So we found a cardboard box and made a Large Flat Shawn to go with the smaller one that jumped off my printer.

“Goodness, Flat Shawn, if these are going to fit you, we need to make a full-boy-sized version of you,” I said. So we found a cardboard box and made a Large Flat Shawn to go with the smaller one that jumped off my printer.

“I can have even more fun now!” he said.

After breakfast he went out on the deck with Bear, my Alaskan Husky dog. “You are right!” he said. “I’m really warm with all this stuff on.” He jumped up on the Adirondack chair and I took his picture with Bear. He and Bear had fun running around in the snow.

Flat Shawn Rides a Water Truck

While they were playing, the water truck arrived, and Flat Shawn watched while the driver, an Eskimo man named Charles, filled our water tank. “You know, Shawn,” he said, “Bethel is very different from where you live. Most people here don’t have pipes that bring water to their houses and carry sewage away. Each house has its own water tank and sewer tank, and every week a truck like this big one here comes to the house and fills up the water tank. A different truck comes and empties out the sewer tank. People have to be very careful not to waste their water, or they might run out.”

Flat Shawn’s eyes were round with amazement as he looked up at the giant truck. “Could I ride in the truck with you?” he asked Charles.

“Actually, the truck is almost empty and I was just heading back to the pump house to fill it up so I can continue my deliveries. The house next door is my next stop, so I’ll be back in about twenty minutes. If it’s OK with The Tundra PA, you could ride to the pump house with me and watch the truck get filled up, and then I’ll bring you back.” Charles smiled at me and I nodded. Flat Shawn climbed up into the truck’s cab quick as a flash.

“And that’s a mighty fine beaver hat you’ve got on, too,” I heard Charles say as they drove off. “You look like a real Alaska boy.”

In a short time they were back, and Flat Shawn jumped down from the truck and waved as Charles drove on to the next house on his route. “Look!” he said to me. “One of the guys took my picture with Charles while the truck was being filled. We can add it to my report about Alaska.”

In a short time they were back, and Flat Shawn jumped down from the truck and waved as Charles drove on to the next house on his route. “Look!” he said to me. “One of the guys took my picture with Charles while the truck was being filled. We can add it to my report about Alaska.”

The snow that started falling while they were gone was turning into a real blizzard, so we went back inside. “This is not good weather to be outside,” I told him. “Let’s learn some things to prepare for the adventure you are going to have tomorrow.”

Flat Shawn Goes Dog Mushing

“I love learning new things. What are we going to do tomorrow?” Flat Shawn asked.

“Well, tomorrow we are going dog mushing,” I responded. Flat Shawn’s eyes sparkled. “Dog mushing is the state sport in Alaska,” I told him. “Back in the old days, before snow machines were invented, that was how the Eskimos traveled around. Most families kept a team of dogs that were trained to pull a sled. The whole family could ride in the sled, and they often traveled long distances that way. Sometimes they would hold races to see who had the fastest dogs.”

“Today there are lots of sled dog races around Alaska, but the most famous one is the Iditarod. It is a race of almost 1100 miles from Anchorage all the way to Nome, held every year in March. The winning team will finish in about nine days. Each team starts with 16 dogs pulling a sled with one musher. The musher must take very good care of the dogs so they can run that far. It is hard work, but the dogs really love it. They have thick fur coats to keep them warm and strong bodies to pull the sled. The musher trains them all year long so they will be ready for the race. It is exciting to watch a good dog team at work.”

I put a video into the recorder about a previous year’s Iditarod, and Flat Shawn watched closely to see how the teams and mushers worked together. “If your school has internet access, your class might want to follow the Iditarod when it is run next March,” I told him. “There is a whole program for school children about it, with activities and lots of fun stuff to do." He wrote down the website www.iditarod.com and taped it to his shoe.

“My friend Henry is a dog musher, and he is going to take us mushing tomorrow,” I told him. “It won’t be a race; we’ll just go out with his dog team and get some fresh fish from his fish net. You can ride in the sled, and my friend Dutch and I will go on snow machines. You can drive the snow machine on the way home, too.”

“But I don’t have a driver’s license!” Flat Shawn said. “And I don’t even know what a snow machine is,” he added.

“That’s OK,” I told him. “I’ll show you, it’s easy. Most people in the lower 48 call them snowmobiles. Kids up here start driving small ones when they are about five or six years old. You’ll catch on quickly, I’m sure.”

The next day is sunny and bright and a little warmer, about ten degrees above zero. We warm up the snow machines and put Flat Shawn’s smaller version of himself in the backpack for the trip over to Henry’s. When we arrive at Henry’s house he has the sled ready and is hooking eight dogs up to the gangline that pulls the sled. He has over twenty dogs, and each one hopes to be chosen for the team. They are all barking excitedly, and it is pretty noisy for a while. Flat Shawn jumps in the sled, Henry says “Let’s go, dogs!” and they take off. Dutch and I follow behind on our snow machines, keeping the team in sight.

The next day is sunny and bright and a little warmer, about ten degrees above zero. We warm up the snow machines and put Flat Shawn’s smaller version of himself in the backpack for the trip over to Henry’s. When we arrive at Henry’s house he has the sled ready and is hooking eight dogs up to the gangline that pulls the sled. He has over twenty dogs, and each one hopes to be chosen for the team. They are all barking excitedly, and it is pretty noisy for a while. Flat Shawn jumps in the sled, Henry says “Let’s go, dogs!” and they take off. Dutch and I follow behind on our snow machines, keeping the team in sight.

Once the team leaves the yard, all barking stops and it is quiet. The dogs are working now, and focused on their job. Each dog wears a harness and they are attached to the gangline in pairs. The two leaders are in front; behind them are the swing dogs, then two team dogs, then the two dogs just in front of the sled who are the wheel dogs. Wheel dogs have to be extra strong, because it is their job to keep the sled from bouncing sideways when the trail is rough or uneven. They all work together, running smoothly. The leaders follow commands from the musher to follow the trail. Gee means to turn right, haw means to turn left, and whoa means to stop.

It is about ten miles to the place where Henry has a fish net under the ice. The Kuskokwim River is frozen hard, and the ice is about eight inches thick. By the end of December the ice will be two to three feet thick, and cars and trucks will be able to drive on it. But for now, there are only snow machines, four-wheelers and dog teams traveling on the river.

Flat Shawn Goes Ice Fishing

It takes us about an hour to get to the fish net. Henry stops the dogs and jabs his ice hook into the frozen river to hold the dogs so they can’t take off on their own. Dutch and I park the snow machines nearby. Flat Shawn jumps out of the sled and looks around with wonder. “This is really the wilderness, isn’t it?” he says. And he is right. We can see miles in every direction and there is not a single person anywhere. No buildings, no houses, no sign of human life.

Two tall sticks are frozen into the ice marking each end of the fish net. Henry pulls out his ice chisel and starts chipping a hole next to one of the sticks. It takes a while, but eventually he makes a hole in the ice about two feet across. Cold river water sloshes in the hole. Then he does the same thing next to the other stick. We tie a long rope to one end of the fish net and start dragging the net out through the hole. “Holy cow!” Henry says. “Look at all the fish!” By the time the net is out of the water we have 29 fish. That’s a really big catch; usually there are only eight or ten fish. Winter is not the season for salmon; these are whitefish and lushfish. Whitefish are tender and tasty, much like cod; lushfish are bottom feeders like catfish, and are kind of pre-historic looking. I like whitefish the best.

Two tall sticks are frozen into the ice marking each end of the fish net. Henry pulls out his ice chisel and starts chipping a hole next to one of the sticks. It takes a while, but eventually he makes a hole in the ice about two feet across. Cold river water sloshes in the hole. Then he does the same thing next to the other stick. We tie a long rope to one end of the fish net and start dragging the net out through the hole. “Holy cow!” Henry says. “Look at all the fish!” By the time the net is out of the water we have 29 fish. That’s a really big catch; usually there are only eight or ten fish. Winter is not the season for salmon; these are whitefish and lushfish. Whitefish are tender and tasty, much like cod; lushfish are bottom feeders like catfish, and are kind of pre-historic looking. I like whitefish the best.

We feed the net back into the water and reattach the net to the sticks, then fill in the hole. Henry will come back every two days to empty the net again.

Flat Shawn helps me count the fish and put them in a big bag that Henry brought. We load the bag into the sled while Henry gives the dogs a snack of frozen meat. We drink some hot chocolate and eat sandwiches that I brought, and then it is time to go back to Bethel.

Flat Shawn Drives a Snow Machine

Flat Shawn Drives a Snow Machine

Flat Shawn looks over at the snow machines and says, “can I really drive that thing?” “Sure,” I tell him. “Sit on it like a motorcycle and squeeze the lever on the right handle and you’ll go forward. Steer it just like a motorcycle or a bicycle. Squeeze the lever on the left handle and you’ll stop. It is that simple.” Flat Shawn gives it a try and finds that it really is easy, and lots of fun. He sits in front of me on my machine and does some of the driving on the way back.

The trip home is quick, and Flat Shawn is proud of his driving. “You did a really good job,” I tell him. “You’re an honorary Alaskan now!”

The next morning we finish writing his report to the class about his trip to Alaska. “I guess it is time to go, isn’t it?” he says. “I had a really good time.”

“I’m so glad you could come for a visit, Flat Shawn,” I tell him. “And I hope you learned a lot about our 49th state. It is a wonderful place. Like our state motto says, it is The Last Frontier. Perhaps some day you and your family can visit here in your real selves. Until then, send your flat self on up anytime you wish!”

He gives me a quick hug and then jumps in the package with his report to the class. I take him to the post office and wave good-bye as the postmaster sends him Air Mail back to Mobile.

THE END

Photo Credits:

1. Flat Shawn by Shawn

2. Denali (mt-mckinley-reflected.jpg from www.jhk1.nl/page/picspag/pics5.html)

3. Tracy catches a king salmon by The Tundra PA

4. Northern lights (northernlights98.jpg from www.omineca.bc.ca/free.html)

5. Polar bears (3lazypolarbears.jpg from www.soulcysters.net/showthread.php?t=112924)

6. Flat Shawn & Bear by The Tundra PA

7. Flat Shawn with Charles and the water truck by The Tundra PA

8. Henry & dogteam crossing Hangar Lake by The Tundra PA

9. Flat Shawn helps count fish by Dutch

10. Flat Shawn drives sno-go by The Tundra PA

Labels: Tundra Life